November 25, 2024

This short report presents trends on increases in total property tax extensions for all the governments on typical Chicago property tax bills. A taxpayer in the City of Chicago pays property taxes to 7 or 8 local governments, depending on which part of the City they live.

An extension is the total amount of property tax revenue a government receives after applying tax extension limitations and rate limits. Property taxes in a particular tax year are payable in the following year. So, taxes levied in tax year 2023 are payable in 2024. In effect, a property tax extension is the financial burden on property owners.

Detailed information about the Cook County tax extension process can be found in the Civic Federation’s primer here.

Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson originally proposed a $300 million property tax increase to help close the City’s FY2025 $982.4 million budget gap. The City Council unanimously rejected the proposal on November 13, 2025. Since then, the mayor has reduced his request for a property tax increase to $150 million with mixed reviews from Council members. At the time of publication, it is unclear how this issue will be resolved.

About Property Taxes

The property tax is an ad valorem tax, which is a tax on the value of property. This tax is a major source of revenue for local governments such as municipalities or school districts.

Governments rely heavily on this tax because it is a relatively stable source of revenue. It is inelastic as, unlike sales or income taxes, collections in most jurisdictions tend not to fluctuate with changes in economic conditions. In addition, a very high percentage of property owners typically pay property taxes when they are due. If they fail to do so by the payment deadline – typically two and a half years for personal property and one year for commercial property – a tax buyer can go to court and obtain ownership of the property.

Despite their high rate of on-time payment, property taxes rank among the least popular taxes, as they are imposed on an unrealized capital gain, which is the increase in value of the taxpayer’s property. Because the tax is based on the property value, not the owner's income, a homeowner or business owner’s property tax bill can rise even if the taxpayer’s cash position declines. This can be particularly burdensome for taxpayers living in areas experiencing rapidly increasing property values.

Cook County property tax bills are sent to property owners in two installments. The first, which is 55% of the prior year’s total tax bill, is due in March. The second bill, due in August, accounts for the remainder of property taxes owed as determined by government extensions for the upcoming tax year. Unlike other taxes paid throughout the year at the time of purchase or deducted from paychecks, the bills are highly visible and widely reported on – factors that contribute to their unpopularity.

Finally, Cook County is divided into three assessment districts; one-third of the County is reassessed every third year. The reassessment process adjusts the value of property for taxation purposes based on estimates of changes in real estate market value. Depending on several variables, such as changes in market conditions, the valuation of similar properties, and the degree to which governments increase their property tax extensions, property owners may experience significant increases in the property’s assessed value and, correspondingly, their property tax bills.

Property Tax Extension Trends Between Tax Years 2014 and 2023

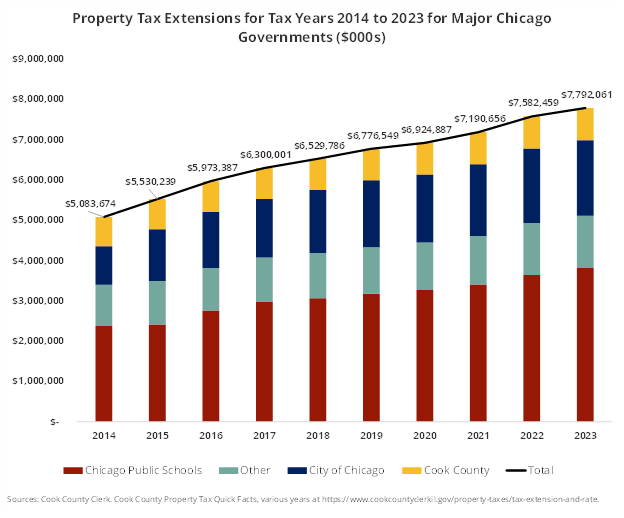

The chart below shows the total amount of property tax extensions between tax years 2014 and 2023 for the seven major governments on the typical Chicago property owner’s tax bill. These include:

- Three major governments: Chicago Public Schools, the City of Chicago, and Cook County, which averaged over 82% of all property tax receipts in the years reviewed. Data is presented individually for these governments.

- Four smaller governments: City Colleges of Chicago, Chicago Park District, Forest Preserve District of Cook County, and Metropolitan Water Reclamation District. Data for these governments is aggregated under the “Other” category in the chart.

Chicago residents living south of 87th Street also pay property taxes to the South Cook Mosquito Abatement District. Additionally, there are special service areas scattered throughout the city where taxpayers have agreed to pay more property taxes in order to receive enhanced services.

Two of the governments reviewed – the City of Chicago and Cook County – are home rule governments without legal limits on the amount they can increase property taxes per year. However, Chicago does have a self-imposed property tax cap that limits the rate of growth in the levy to the lesser of 5% or the growth in the Consumer Price Index (CPI), with some exceptions for debt service, pensions, expiring tax increment financing (TIF) districts and new property. Cook County has held its base property tax level flat at $720.5 million since 2001 but does collect some additional property tax revenue from expiring TIF districts, new property, and expiring incentives.

The other taxing bodies are non-home rule governments, which can only increase property taxes annually by the 5% “Tax Cap” or the rate of inflation, whichever is less under the state’s Property Tax Extension Limitation Law (PTELL), with some exceptions for non-capped funds such as debt service, new property, annexed property, recovered tax increment financing district increment, and expired incentive value.

Property Tax Trends Between Tax Years 2014 and 2023

Information about major Chicago area government property tax extension trends is presented below. In the ten-year period reviewed:

- The total property tax burden rose by $2.7 billion, or 53.3%, between tax years 2014 and 2023. This increased from $5.1 billion to $7.8 billion.

- During this same period (calendar years 2015 and 2024), inflation rose by approximately 35%, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

- The Chicago Public Schools increased property taxes from $2.4 billion to $3.8 billion, a 60.6% or $1.4 billion increase. Much of the increase is due to the reinstatement of a dedicated property tax levy to fund teacher pensions in FY2017. The pension levy was reinstituted beginning in FY2017 at a tax rate of 0.383%; the rate was increased to 0.567% in FY2018. This has allowed CPS to receive additional property tax revenue outside the PTELL tax cap. In the first year of implementation, this additional revenue was approximately $250 million; it grew to $557.1 million in FY2024.

- The City of Chicago increased property taxes from $956.12 million to $1.8 billion, a 96.4% or $921 million increase. Much of this increase was due to a state statutory requirement to increase funding for the City’s historically underfunded pension funds and to put their funding on an actuarial basis. The portion of the extension dedicated to pensions alone rose from $67.1 million in FY2015 to $1.4 billion in FY2024.

- During the same period, other taxing districts increased property taxes by $275.0 million, or 26.9%, rising from $1.0 billion to $1.3 billion.

- Cook County’s government property taxes rose by 9.9%, increasing from $728.2 million to $800.6 million.

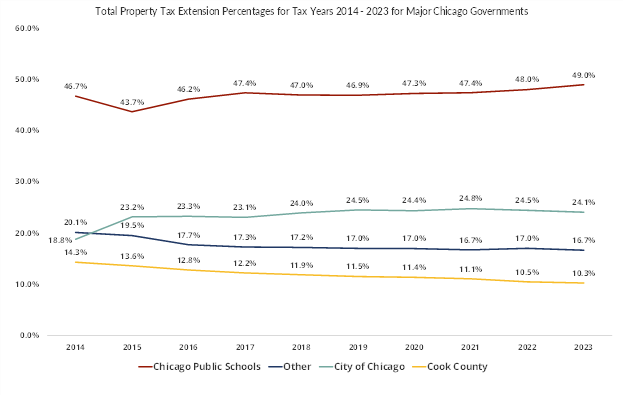

The following chart shows the percentage of total property tax burden per government for tax years 2014 through 2023. Chicago Public Schools' share of total property taxes rose from 46.7% to 49.0% in the period reviewed. The City of Chicago’s percentage of total extensions increased from 18.8% to 24.1%. The four “Other” governments’ property taxes declined from 20.1% to 16.7%, while the Cook County share fell from 14.3% to 10.3%.

Changes in Chicago Property Tax Bills Between Tax Years 2014 and 2023

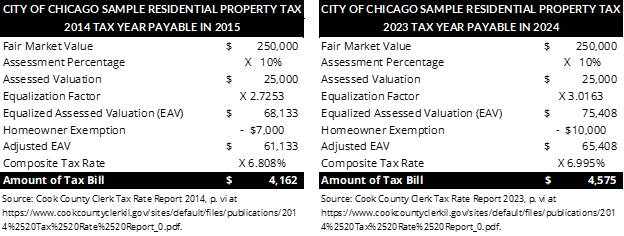

Property tax bills are calculated according to the following formula:

- The Cook County Assessor’s Office determines a property’s fair market value (what it would sell for in the marketplace).

- An assessment percentage is applied. In Cook County, residential property is assessed at 10% of fair market value.

- An equalization factor established by the Illinois Department of Revenue is applied. The equalization factor is used to achieve uniform property assessments throughout the state.

- The assessed valuation multiplied by the equalization factor yields the property Equalized Assessed Valuation (EAV) or the taxable value of the property.

- Then, a homeowner’s exemption for primary residences is applied, reducing the property's taxable value. In 2014 it was $7,000. The exemption was increased to $10,000 in 2015.

- Subtracting the homeowner’s exemption from the EAV yields an adjusted EAV.

- Finally, a composite property tax rate, which totals the tax rate of all seven or eight governments imposing levying property taxes on that property, is applied to yield a tax bill. In 2014, the rate was 6.808%; by 2023, it had risen to 6.995%.

Information about how Cook County property tax bills are calculated can be found here.

As the charts below show, a sample property tax bill for a home worth $250,000 in tax year 2014 was approximately $4,162. It rose to $4,575 in tax year 2023.